In 2020, his first book Isaac (Grasset) lifted the veil on his great-grandfather rabbi through a family inquiry around the silence that followed the Shoah in France. In 2021, she still addressed the issue of memory around this period of history with “The voice of witnesses”, working with the Shoah Memorial. Last year, she wrote for the INA a series in four episodes around the 5:30 long interview with Simone Veil.

Today, Léa Veinstein focuses on the plunder of cultural property during the Nazi period. She is the director of the six episodes of “On the Trail”in which she reviews six works or groups of works studied by the Mission of search and restitution of plundered cultural property between 1933 and 1945 of the Ministry of Culture. This podcast is one of the the Year of Documentary 2023, launched last January.

For about twenty minutes, the listener plunges back into the past thanks to the sound archives, pushes the door of the museums, listens to pages of inventory turn, imagine the paintings described. To accompany her story, the voice of the actress Florence Loiret-Caille who follows and tells each story, those of François Pérache and Caroline Mounier to read the archives, not to mention the sound production of Arnaud Forest. Look back on this meticulous work of realization.

You are accustomed to subjects on memory and more particularly on the testimonies of the Shoah. How did you end up working on this project?

Lea Veinstein: The mission of restitution had this idea of podcast to communicate in another way about his work. For a long time, the French state was criticized for not taking care of these works of art resulting from the dispossession. This has not been the case for some years and the will is now to change our view of the role of the State. This willingness was the starting point of the series. Then the mission knew my work through the exhibition for the memorial of the Shoah with a sound path and for which I had done a podcast on a story of testimony. So the department has offered to think about this series.

I knew there had been the Mattéoli Commission (Study Mission on the Dispossession of the Jews of France installed in 1997, ed.) created under Jacques Chirac and which brought together historians and researchers on the issue of reparations, particularly financial. I had also heard about this at the Shoah Memorial which had done a great exhibition on the art market under the Occupation where the institution talked about forced sales and how families were stolen. But I discovered all the details of these spoliations during my research by doing the podcast.

Precisely, how did you prepare each of these episodes beforehand?

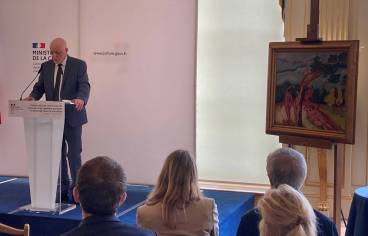

L.V.: I had some interlocutors as well as written documents, summary notes, paper archives to soak up each story. Then we established with the Mission a list of people to interview, places to go, situations in which I wanted to record, such as restitution ceremonies. There is usually in each episode a researcher and, where possible, a rights holder. It was then necessary to block the shootings and when I had all the material, I started writing the episode. Finally the sound director added music and ambiances.

The work of art is also

a historical witness

Each episode, lasting about 20 minutes, is constructed as a police investigation, with a lot of emphasis on details, description…

L.V.: There is in fact this “investigation” aspect that we wanted to restore and which lends itself well to podcast because it is fully part of the mission’s work. Second, podcast is, by definition, sound. When only one of our senses - in this case hearing - is in action, we need it to be solicited so if we want to take the listener with us, the sound must be alive.

This is why I vary the registers to the maximum, from an archive to a living situation of restitution; in the ear of the listener, it translates into a brouhaha then an older sound then a voice of today that explains something before going back to an archive. The subject is heavy, the stories complicated, so it takes life, movement, that one finds by the sound. I think there is a need for all this to make the stories alive.

In the book you have written and the podcasts you have made, you are very interested in testimony, memory and transmission. How is telling the story of these works of art another testimony of this time?

L.V.: I completely share the idea that the work of art is also a historical witness and it even surprised me to feel it so much. When I started working on this project, I had an understanding of the historical context in which these stories and issues of memory take place. This podcast is however not really a historical podcast but rather a podcast about what memory is. Of course, there are passages that recount the spoliations because we are in the historical register, but the stories that are told are those of these works of art, how they got there and how they come back to the families today. The issue is that of repair through objects.

Something happened that really touched me and I never imagined. When you work for example on the testimony of Simone Veil, you have the voice, the incarnation by someone who tells what he lived. When you find yourself in a moment of restitution, you see the work of art as a witness, with such a strong presence. When we talk about art, there is the notion of beauty, but for all these works, it goes beyond the value of the artist or their financial value.

Making this podcast was also a way to explore and explain to the general public a more unknown facet of the dispossession made by the Nazis?

L.V.: What’s interesting about these six episodes is how perverted and multiple this type of persecution was. Plunder is not just the Nazis, the Gestapo, the ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg organ which carried out from 1940 important confiscations of property belonging to Jews) who arrive in an apartment in Paris, grab it, take everything in it and bring it to the Palm Game. There are also forced sales such as for the Drey family or, in the case of the Klimt, an individual close to the Nazi regime who will hide this aspect of his identity to extract the painting from Nora Stiasny for a completely paltry sum. Today, with the elements we know about the context, the identity of this man and the destiny of this woman who will die deported, we can describe this sale as spoliation. It takes many different forms and that’s what makes investigative work so difficult.

What is the strength of the podcast - and more generally of the sound - when we tell these kinds of stories that touch on memory and intimacy?

L.V.: There’s a very deep connection between listening and memory. It’s personal, but I really believe in it. I always take the example of mourning someone we knew. If you review a video of this person, it will touch you but experience hearing only his voice and you will see that it is ten times more upsetting whereas paradoxically, one could imagine that the image and the movement make the person closer to reality, to who he really was.

I think that in our voice, there is all our presence and when we isolate it, we find ourselves alone in front of this presence. It puts us in and a very strong relationship to memory and for this podcast that deals with memory and how objects go through history, it works very well.

Actress Florence Loiret Caille, voice of «À la trace»

During these six episodes of about twenty minutes, actress Florence Loiret Caille, famous Marie-Jeanne Duthilleul, major agent of the secret services in the series The Bureau of Legends, She is accompanied by two other actors François Pérache and Caroline Mounier as they read the archives. The sound design was entrusted to Arnaud Forest, a sound engineer by training, notably to Arte Radio, ARTE’s web radio. Finally, the last actor of this podcast: the Gong production studio, which produces original creations from design to production, mixing and music.

Partager la page