Crossing time with the Mâconnaises collections

The Ursuline Museum in Mâcon holds a rich and diverse collection of more than 25,000 works that provide a panorama of the history of art from antiquity to the 20th century. Discover them through these four themes, from Roman Gaul to raw art, and through the collections that the museum has put online on Mona Lisa, the collective catalogue of collections of museums in France.

From antiquity to raw art...

> The treasure of Chenôves, late 2nd century-early 1st century BC

> The Treasure of Curtil-sous-Burnand, 3rd century

> Hippolyte Petitjean (1854-1929)

> Johé Gormand (1905-1963), a poetic of raw art

The treasure of Chenôves, late 2nd century-early 1st century BC

The cave of Chenôves has revealed a drama among the Eduens, as well as a treasure that has allowed to define a new iconographic type of numismatic: the type of Chenôves.

Credits: this content was originally published on the Mona Lisa website. It was founded in 2016 by Héloïse Schomas (Mâcon Museums) and Jeannette Ivain of the French Museum Service. The museum’s records are online on POP, an open heritage platform.

Discover the treasure of Chenôves on Mona Lisa

During the winter of 1933-1934, Eugène Guillard, Abbé de Chaudenay, carried out excavations in the cave of Creux Beurnichot, in the town of Chenôves, located in Saône-et-Loire. In Gallic occupation levels, the bone remains of about ten individuals (one or two families), mostly children, were cleared. Other objects were discovered in the stratigraphic unit: shards of pots, bowls and other containers dated to the end of the Second Iron Age, during the Tène III (pre-Roman Gallic period, late 2nd century-early 1st century BC), and some small objects: metal rings, iron fibula, beads. There was obviously looting during the occupation. The bodies were left there without being buried, which suggests a violent death.

In a corridor that escaped looting, a treasure of forty to fifty Gaulish coins was brought to light. The Mâcon Museum holds 42 coins from this treasure: 39 from Abbé Guillard in 1965 and 3 of the landowner 1990. According to the dating of coins and pottery, the treasure was buried in the 1st century BC.

Its component currencies are staters in gold or electrum also dated from Tene III, issued by the Eduens, an important Celtic people settled in the centre-east of Gaul (Allier, Côte d'Or, Nièvre and Saône-et-Loire), whose capitals were Bibracte then Autun - Augustodunum.

The images depicted on the pieces are reinterpretations of staters of Philip II of Macedonia, coins with which some Celtic mercenaries were paid during great ancient conflicts. But the imagery of the Philippe II staters has been recovered and rehabilitated to the cultural criteria of the Celts.

The rights of all these coins are an effigy of very simplified profile, with a fleuron in front of the mouth and a hairstyle with S-shaped locks.

The lapels are based on the systematic representation of a stylized horse with variants: driver in human or bird form, presence of a chariot or not, and various symbols of Celtic art, often between the legs of the horse: a wheel, a triskele, or a lyre.

The discovery of this site revealed a drama among the Eduens, as well as a treasure that helped define a new iconographic type of numismatic: the type of Chenôves.

The Treasure of Curtil-sous-Burnand, 3rd century

In the 3rd century, Roman Gaul experienced a period of great instability that led the notables to bury monetary savings. These treasures are sometimes discovered like that of Curtil-sous-Burnand.

Credits: this content was originally published on the Mona Lisa website. It was created in 2018 by Héloïse Schomas (Mâcon Museums) and Jeannette Ivain of the French Museum Service. The museum’s records are online on POP, an open heritage platform.

Discover the treasure of Curtil-sous-Burnand on Mona Lisa

The monetary treasure of Curtil-sous-Burnand, in Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Burgundy-Franche-Comté, was discovered in 1979-1980, during earthworks of the line TGV Paris-Lyon. It was acquired by the city of Mâcon in 1980 thanks to an exceptional municipal grant and the generosity of the SNCF.

The treasure consists of 84 Antoninian coins, Roman coins in good condition, ranging from the reign of the Roman emperor Gordian III 238 to 244, to that of Gallian 238 to 258. These were coins of considerable value at the time, first made in silver then in billon (alloy of silver and copper). There are no less than 18 portraits of emperors and empresses for the whole treasure which presents the characteristics of the treasure of hoarding, sort of savings.

During the reign of Gordian and until the end of the 3rd century, the title (proportion of precious metal) of the Antoninian decreases. According to the law of Thomas Gresham (1519-1579, English merchant and financier) , the creation and circulation of a currency of inferior quality causes the hoarding and recasting of the currency that was previously circulating (to keep more precious metal). This explains the increase in the number of treasures for this period of late antiquity, such as the Macon Treasure discovered in 1764.

The treasure would have been buried at the latest in 259, the Gallian coins providing a terminus ante quem (a deadline). The reasons for the burial are certainly related to the insecurity and barbaric incursions in the middle of the 3rd century, mentioned by the Latin Panegyrics (collection of eleven ceremonial speeches addressed to the Emperor by Gaulish speakers between 289 and 389), perhaps Alamans (confederation of Germanic tribes mainly Sueve). Postume (Gaulish general who was proclaimed emperor in Gaul from 260 to 269) , attacks several bands that descend the Rhone Valley and raises ramparts along the borders of the Empire (257-260).

The treasure, said of Curtil-sous-Burnand, is exhibited at the Ursuline Museum in Mâcon, as is its counterpart in Chenôves for Gaulish coins. Coins are valuable historical testimonies, and other museums also hold collections of numismatics from the same period: Gallo-Roman Antiquities Museum ofAosta, archaeological museum in Dijon, departmental museum of the Hautes-Alpes in Gap, departmental museum Dobrée in Nantes, Alfred Danicourt Museum in Péronne, museum of Soissons, musée Saint-Raymond in Toulouse.

Hippolyte Petitjean (1854-1929)

Independent painter, anarchist, influenced by Puvis de Chavannes, then by Seurat, he participated in the circle of neo-Impressionists in 1886.

Credits: this content was originally published on the Mona Lisa website. It was created in 2016 by Marie Lapalus (Mâcon Museums) and Jeannette Ivain of the French Museum Service. The museum’s records are online on POP, an open heritage platform.

Discover the work of Hippolyte Petitjean on Mona Lisa

Born in Masthead in 1854, Hippolyte Petitjean is authorized by his father to take courses at the School of Drawing of the city while pursuing an apprenticeship with a painter-decorator. His early talent allows him to obtain a scholarship from the department of Saône-et-Loire to study, in 1872, at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris where he enters the studio Cabin, while admiring the work of Puvis de Chavannes.

Petitjean is independent in his behaviour: anarchist, anticlerical, committed to defending Captain Dreyfus, bohemian, but faithful to the young girl he met in 1879, Louise Claire Chardon - of whom he will have a daughter in 1895, Marcelle –, like his friends Seurat, Luce and the family Pissarro. His participation (under the pseudonym of Jehannet) in the anarchist brochures and posters of the New times of Jean Grave shows his unwavering commitment to causes that seem just to an entire generation. Commitment libertarian merges with the practice of neo-Impressionism: most of the participants worked for the anarchist cause. This circle of artists and personalities in which Petitjean works also serves his national and international career, making it possible to export his work to Belgium and Germany.

Petitjean was a participant in the Salon des Indépendants from 1891, and was a recognized artist in the middle of the first circle of neo-Impressionists.

He took the time to write down climatic and botanical information on his sketches, in his correspondence or in his Journal des voyages (1891). It also pays attention to the vernacular architecture, in hills of the know me where he returns in summer and in his discoveries of the landscapes of theIle-de-France. A few trips took him to the South in 1900, at Banyuls at Maillol or in Holland in 1913.

The construction of his house on the edge of Parc Montsouris, in 1904, became the heart of a system where work in the workshop alternated with excursions on foot or by bicycle. The diversity of techniques used for landscape, as for portraits, also illustrates the great freedom of his artistic approach. Hippolyte Petitjean was essentially an artist of theintimacy as evidenced by many works (charcoal and blood).

The synthesis of his interests leads him to a completely personal elegiac painting (Virgilian influence). He also discusses mythology in Bacchanales that will lead him to La Spring dance, first stage from 1905 of a series on the seasons. Then, in a limited corpus, he lengthens the arabesques of his pointillist bathers which he devoted himself to until his death in 1929.

Johé Gormand (1905-1963), a poetic of raw art

In 2011-2012, the city of Mâcon presented at the Ursulines Museum an important donation of the works and writings of Johé Gormand, painter and sculptor, which can be linked to raw art.

Credits: this content was originally published on the Mona Lisa website. It was created in 2012 by Benoît Mahuet, under the direction of Marie Lapalus (Mâcon Museums) and Jeannette Ivain of the French Museum Service. The museum’s records are online on POP, an open heritage platform.

Discover the work of Johé Gormand on Mona Lisa

A singular artist

Around the sculptor Maxime Descombin and the Mâcon School of Art, an intense artistic activity developed immediately after the war. The artists who frequent Johé recognize the originality of his approach, are moved by the spontaneity and depth of his work. The museum will bring his creations into the collections thanks to a major donation made in 1970 of his works and writings.

A native of Cortambert, near Cluny, Johé Gormand lived for some time in Paris before returning to his native land in June 1940. She expresses herself, in extreme poverty, through sculptures in vine wire and cement, paintings made on cloth, cloth or canvas of jute sewn between them and stretched on frames summarily built, drawings in ink of China or watercolour.

She transcribed strange visions tinged with an ideal in the image of the humanism of Saint Francis of Assisi or Don Quixote. His cosmogony generates as many Sancho Panza as Mao, Lenin or Prometheus.

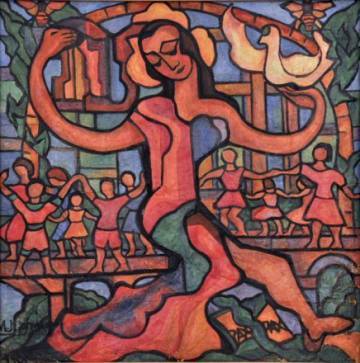

No doubt traumatized by the war, she tackles the realization of an important series of watercolours dedicated to popular dances symbolizing a gigantic Peace Round.

His work

His artistic experience begins to Paris and ends at Toury, near Cluny. Through the representation of thepublic space and of the folk dance, each work is intimately linked to the representation of the crowd, to the song of the peoples whose fraternization it hopes for.

Johé Gormand has always been associated with raw art by artists, amateurs and art critics, curators, (Maxime Descombin, Doctor Joly, René Déroudille and Emile Magnien) who have frequented it, followed and recognized in the singularity of its experience.

His strange work, carried out between 1940 and 1963 in extreme poverty, seems just as destined to accomplish the «purifying mission» that his ethical commitment dictated, as to revere a cosmogony of political figures or of deities and to erect dancers, knights on the road, animals or fairies as messengers of Peace.

The angry Artist, «torn between politics and the divine», intentionally creates primitive works made of recovered or manufactured materials: assembly of canvases cut from sheets or bags of jute canvas, wallpaper samples for painting, rough mounting of frames, vine thread, cement and fossils for sculpture, constitute its rudimentary means of expression.

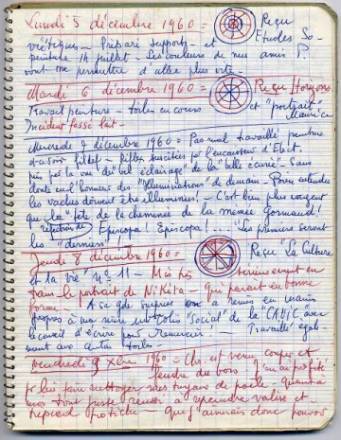

In parallel, Johé Gormand undertakes a literary work as strange as it is rich in information about the daily life of his life. Composed of both day and night notebooks, she describes with great precision the space, the activities of her day, her dreams or her visions. The dark stories of the night respond to the writings of the day; the thoughts and conversations of the day turn into murmurs and hallucinated cries that arise in the shadow of a room of the family home.

A singular work, disturbing, of a single woman, in search of Peace and hiding a great sadness. This sadness and its illusions, perhaps we should seek them in the love of youth that a beautiful Romanian sculptor had taken from him, disappearing after the years of war.

Johé Gormand, isolated, discreet, who hides her work from her mother with whom she lives in Toury, has compiled an abundant iconographic documentation drawn from magazines to which she subscribes - La Chine Populaire, La Chine, Les Etudes soviétiques, Les lettres françaises, Horizons, Culture and Life. - and whose reception seems to be a blessed moment. It is the means for her to remain «in communication» with her «Dear Friends» and to develop a certain illusion of reality.

«I feel a great hope in me. as if I were expecting something happy» she confides in her «Daily Diary»

His biography

February 14, 1905, birth of Marie-Joséphine Gormand (known as Johé). His parents, Joseph Gormand and Jeanne Renaud live in a large house in Toury with pavilion and garden. They are well-to-do farmers and winemakers, who own vineyards and land. His mother also runs the village grocery store. After 1945, the garden and its embellishment will hold an important place in the life and survival of Johé Gormand and his mother.

Around the age of 20, Johé left Clunisois to study at the Conservatoire d'art dramatique in Lyon.

In 1924, his father died in the family home. The family, already affected by the disappearance of the eldest son, found its livelihood compromised.

Johé Gormand left for Paris around 1930 to become an actress. From this period, he met Emmanuel Zalma, a Romanian artist who introduced him to art and the occult sciences.

At the end of the 1930s, she seems to benefit from Montparnasse’s intellectual emulation and participates in the festive atmosphere. This is evidenced by numerous ink drawings, one of which is dated 1939.

In June 1940, the «couple» went to the free zone and took refuge in Saône-et-Loire, in the house of Johé where Zalma hid.

According to family memory, artists never appear together until Zalma left the war. Now alone, Johé Gormand lives with his mother in Toury’s house.

Johé begins a new and singular work whose matrix consists of his dreams and visions. The color is more expressive, more spontaneous, the more direct sign tends towards a primitivism reminiscent of the first paintings of Gontcharova and Larionov, made of forms with pure hues, partitioned by thick black circles like stained glass, whose effect gives his work a supernatural burden.

December 1950: first «exhibition» of his works during a session organized at the initiative of the Friends of Cluny. Johé explains his work there.

In January 1951 and June 1952, exhibitions were organized at the Grange Gallery in Lyon. René Deroudille, a critic from Lyon, who writes the artistic column in the daily «Le tout Lyon», is attentive to his work and personality. The series of folk dances dates from this period. A world tour of the popular dances she performs, symbolizing the brotherhood of peoples she would like to see joined by the hand in a gigantic round.

Around 1954-1955, she discovered the Association des Amitiés Franco-Chinois lyonnaise. Johé is finally in the presence of interlocutors who seem to understand her and share her convictions. Mao becomes for her the personification of the promise of a new era. Now, when she hears: America, she answers: Beijing.

The first portraits of the communist leaders date from this period: Mao as a guardian figure, then quickly Lenin, Stalin, Jaurès, Thorez, Zhou Enlaï. In a kind of syncretism consistent with his community ideal, Johé embraces for his work the diversity of spiritualities: Buddhism and Christianity confront their political ideal.

Johé Gormand tackles an even more disturbing creation: letters addressed to his «Grandfather» and to his «Dear Friends» Chinese fulfill the function of Manifesto.

Then she writes on spiral notebooks that she differentiates in «Diary of night» and «Diary of day». The first, enigmatic, are the description of dreams or visions of the night that seem to be a light guiding his creation. This is probably one of the reasons why she leaves so much room for the evocation of Don Quixote in her work. The latter, methodically begun on June 29, 1958, report daily on his artistic work and his reflections in constant echo of the anger and sadness it contains. They are also the daily witnesses of the outside world.

At the same time, Johé Gormand discovers the sculpture. The poverty in which she lives with her mother in Toury probably explains this late interest. So Johé uses rudimentary means: wire of the vines, recovered or given by his neighbors, quick cement tinted in pink and which she roughly agglomerates on the metal frame.

At that time, there were also many drawings and watercolours depicting the crowd in Parisian public spaces. Back to the sources and to her first drawings. Her contemporaries report that she produced from memory this privileged theme.

In the years 1958-1963, Johé maintained many relations in the village. Thus, visits are not uncommon and his talent as a painter allows him to give some drawing lessons to people in the neighborhood.

Among the unfinished works found in the studio in 1963 is the partial representation of Orpheus. Symbolic self-portrait of a suffering artist.

Johé Gormand died on January 24, 1963 in his home in Toury.

Partager la page